Jay’s Story.

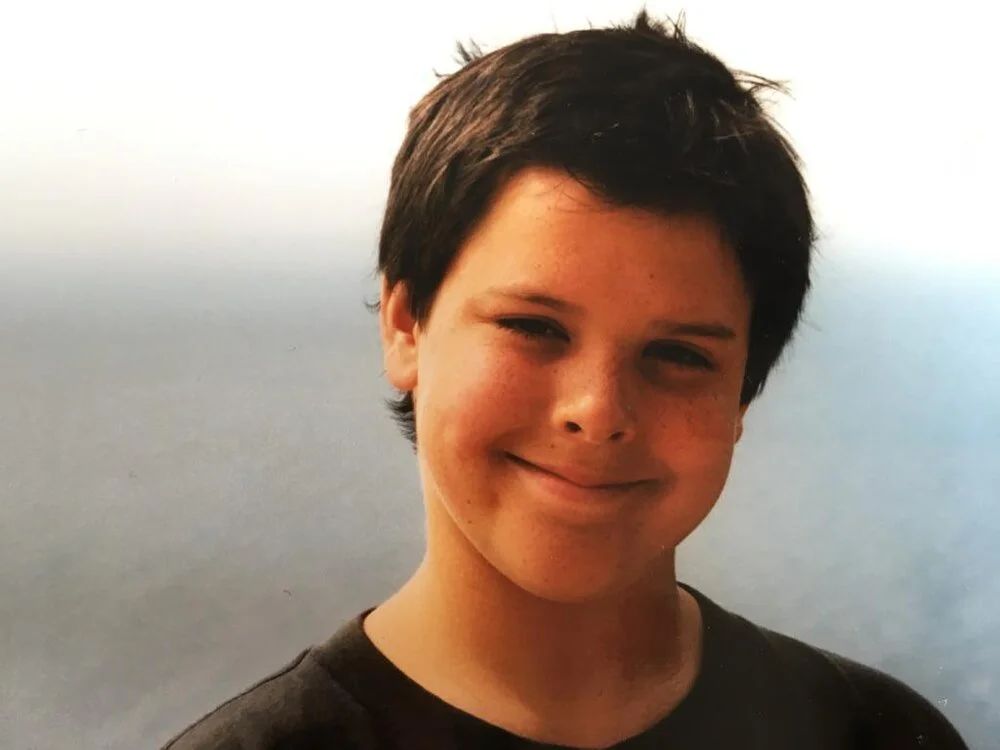

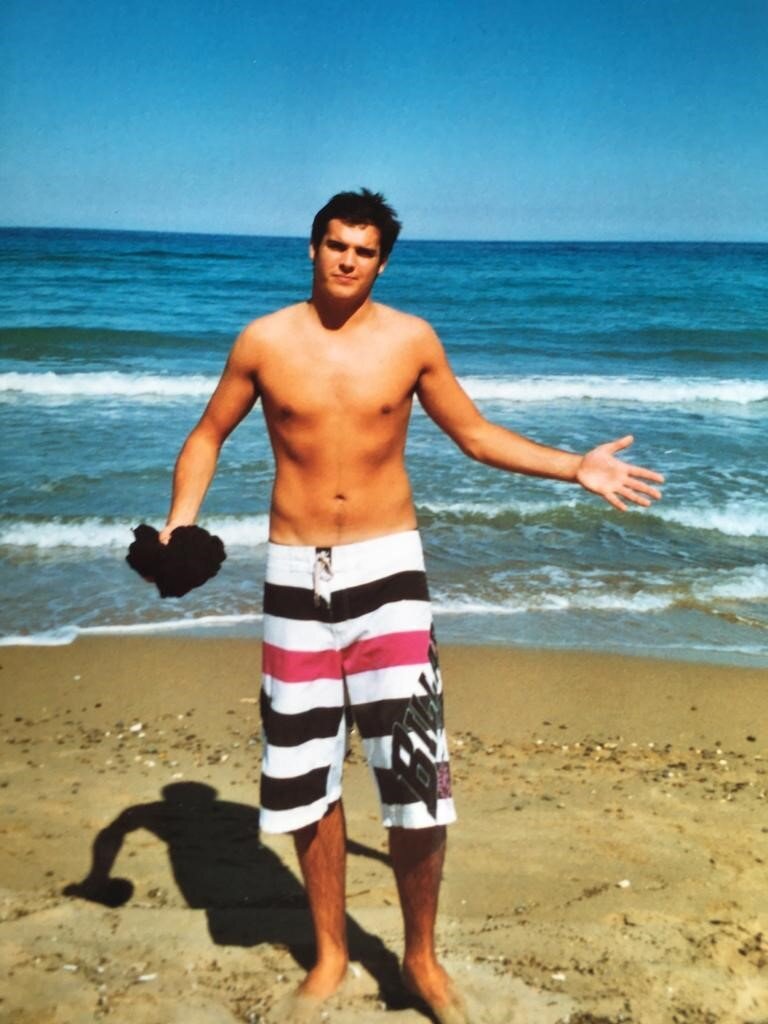

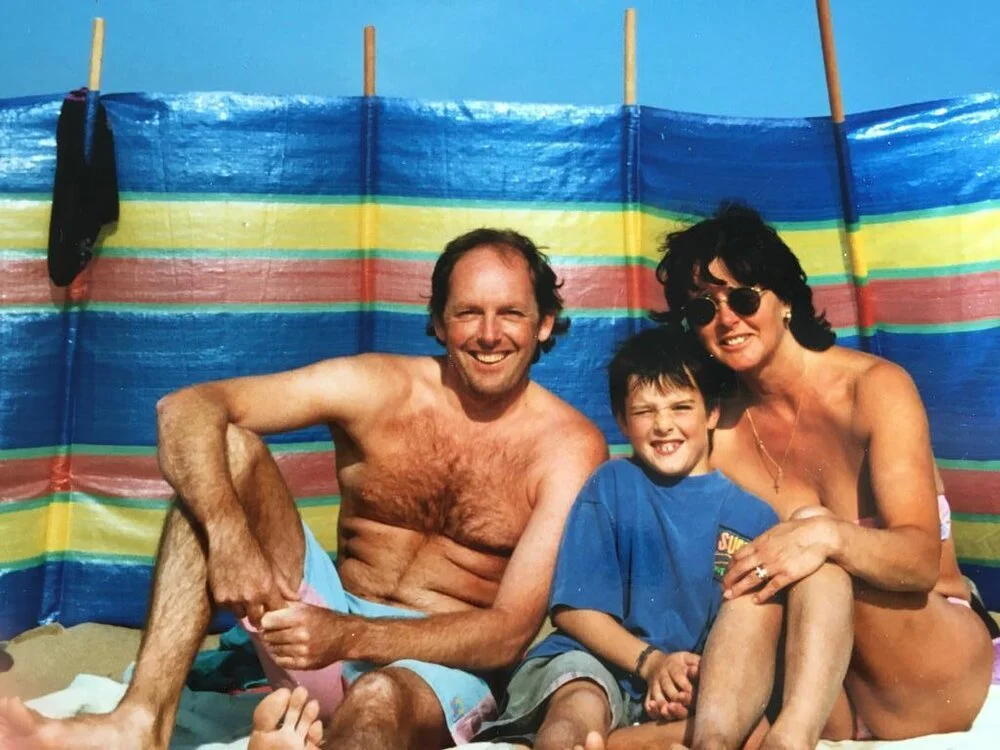

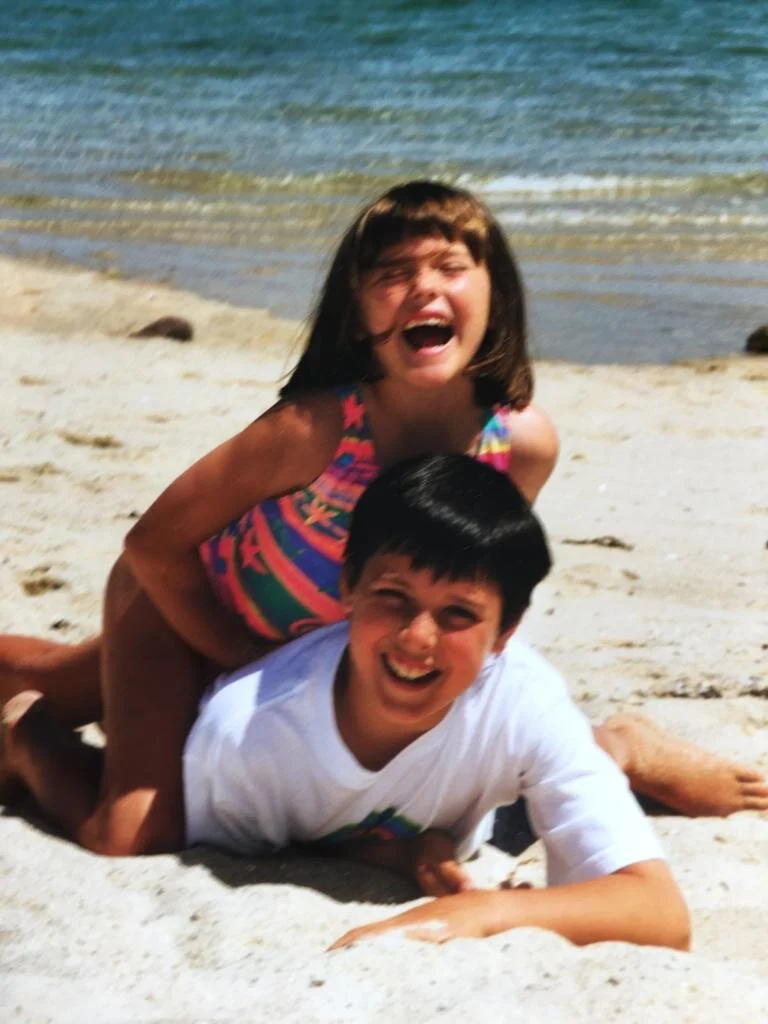

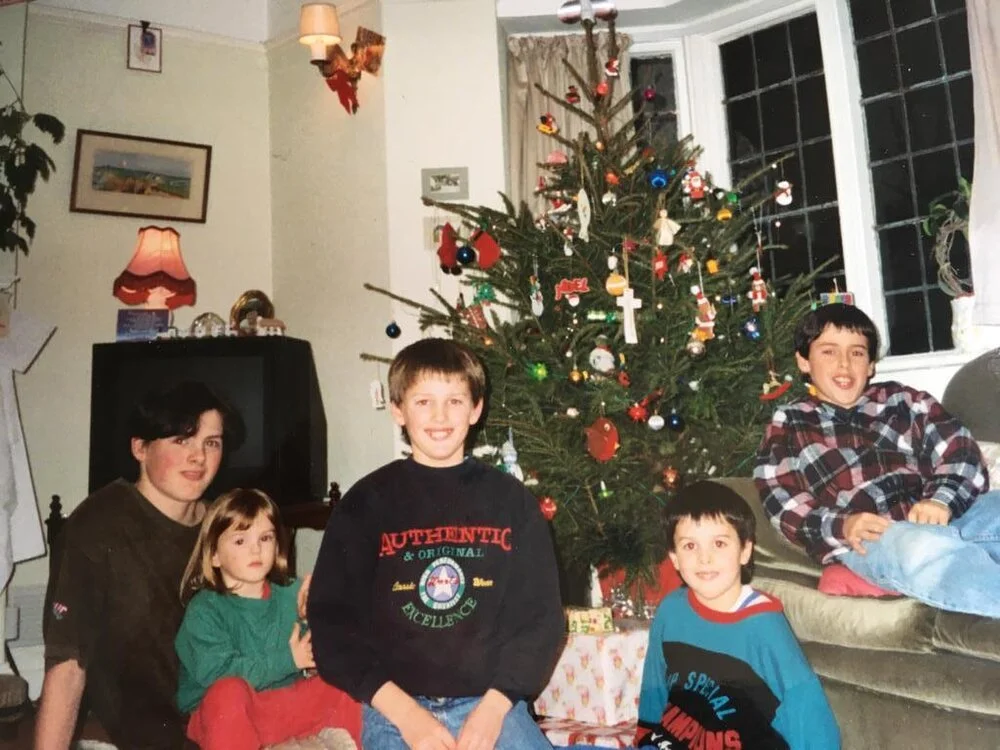

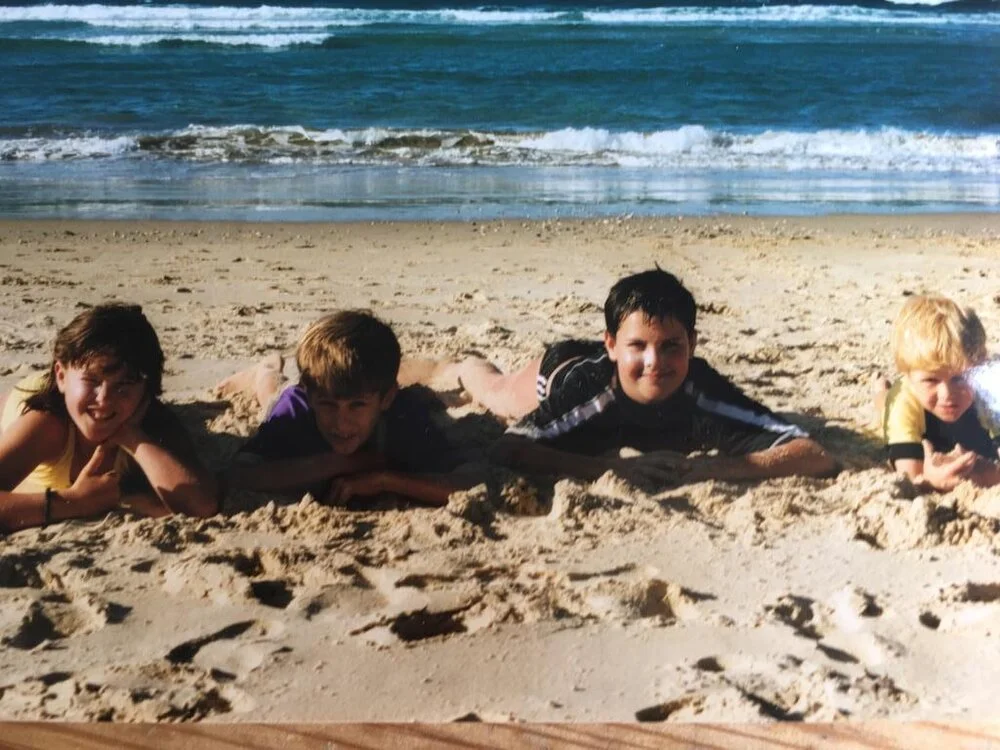

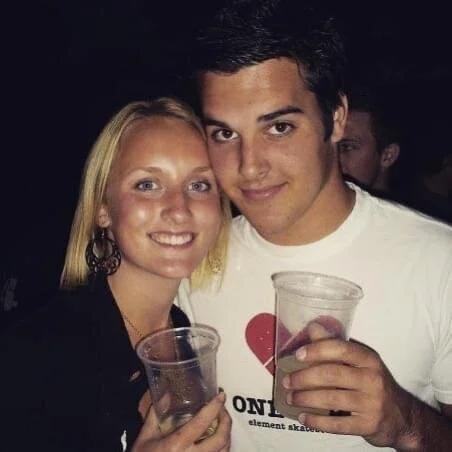

We miss Jay every day. He was a brother, a son, a fiancé and a father who died suddenly and unexpectedly at the age of just 28. After his death, we learnt that Jay had an undiagnosed inherited heart condition, and that this had caused a fatal cardiac arrest.

Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (AC) the condition which took Jay’s life is not well known, and nor are its symptoms. The tragedy is, this heart condition does not need to be fatal; it can be managed successfully if diagnosed correctly in early life.

In loving memory of James (Jay) Alexander Osborne 26/6/88 - 18/6/17

Our story.

Watch our short film that explains why Jay's AIM was set up, what we do, and what we have achieved so far.

The diagnosis.

In the UK, when somebody dies suddenly and without a clear cause, the coroner will request a post mortem examination. In Jay’s case, the post mortem flagged problems with his heart; further investigation at St George’s Hospital, London, showed he had been living with undiagnosed Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (AC). As a family, we’d previously had no idea that Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (AC) existed, let alone that it could be inherited. Suddenly we found ourselves facing not only losing Jay, but also the frightening realisation that this condition might be affecting other members of our family, including children.

As Jay’s first-degree relatives (meaning parents, full siblings and children) we were swiftly contacted by our local cardiology departments and invited to attend a series of cardiac tests. Although the tests came in the midst of grief, the rigorous screening process ended up providing us with some comfort; Jay had lost his life, but in doing so he had given us a new awareness of Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (AC) and the knowledge to protect ourselves.

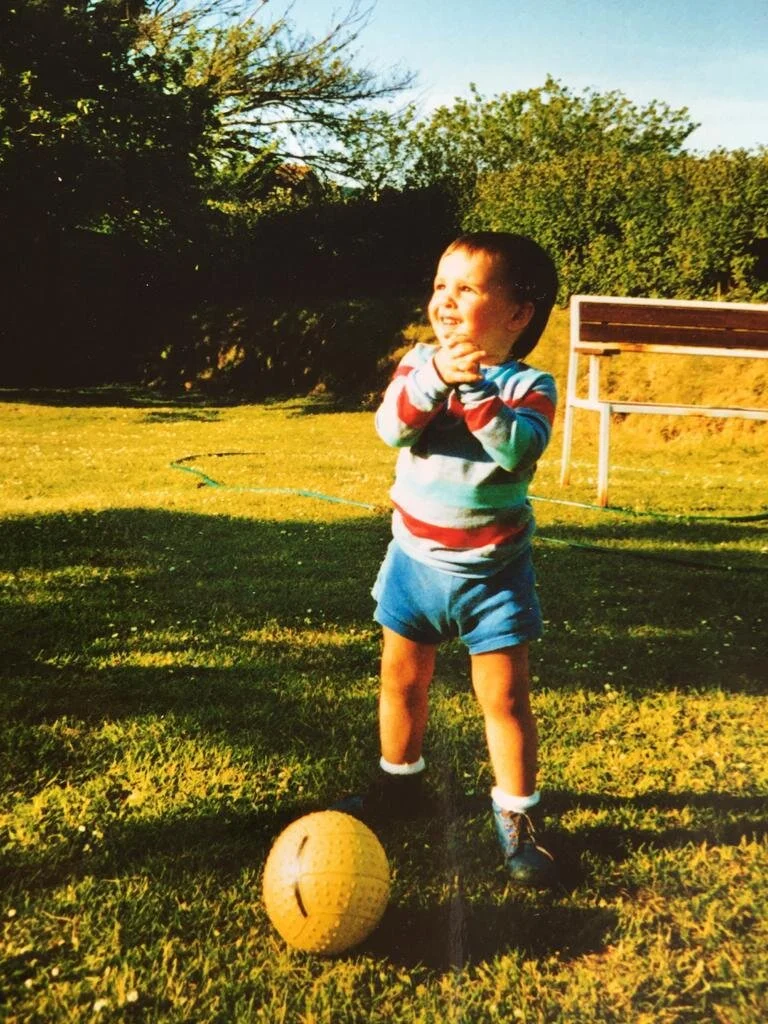

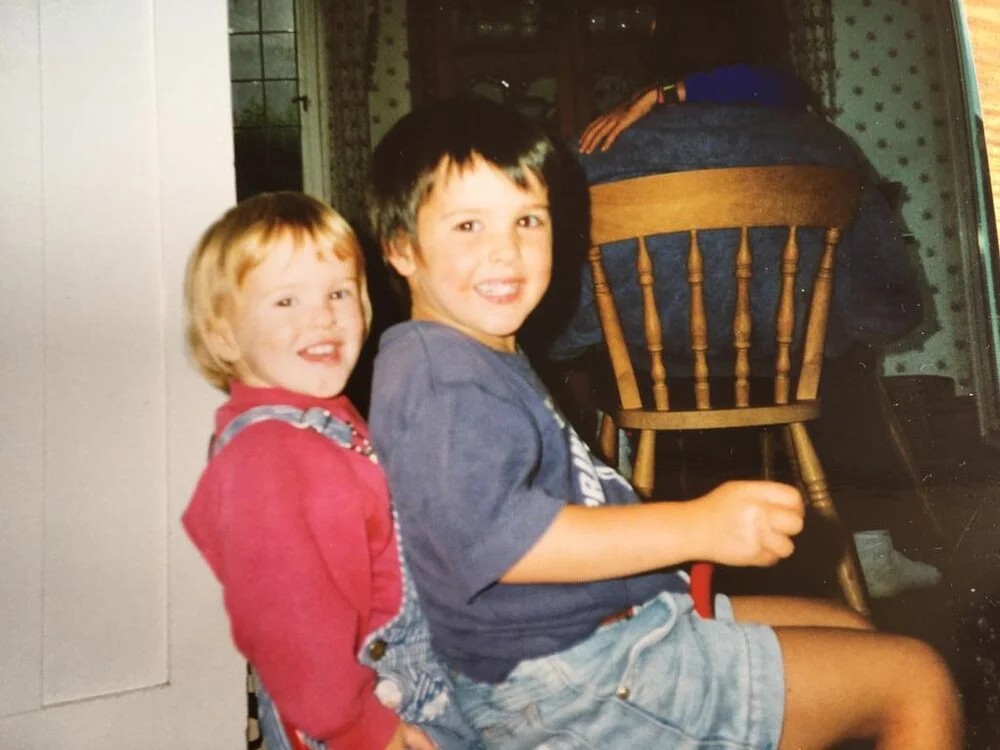

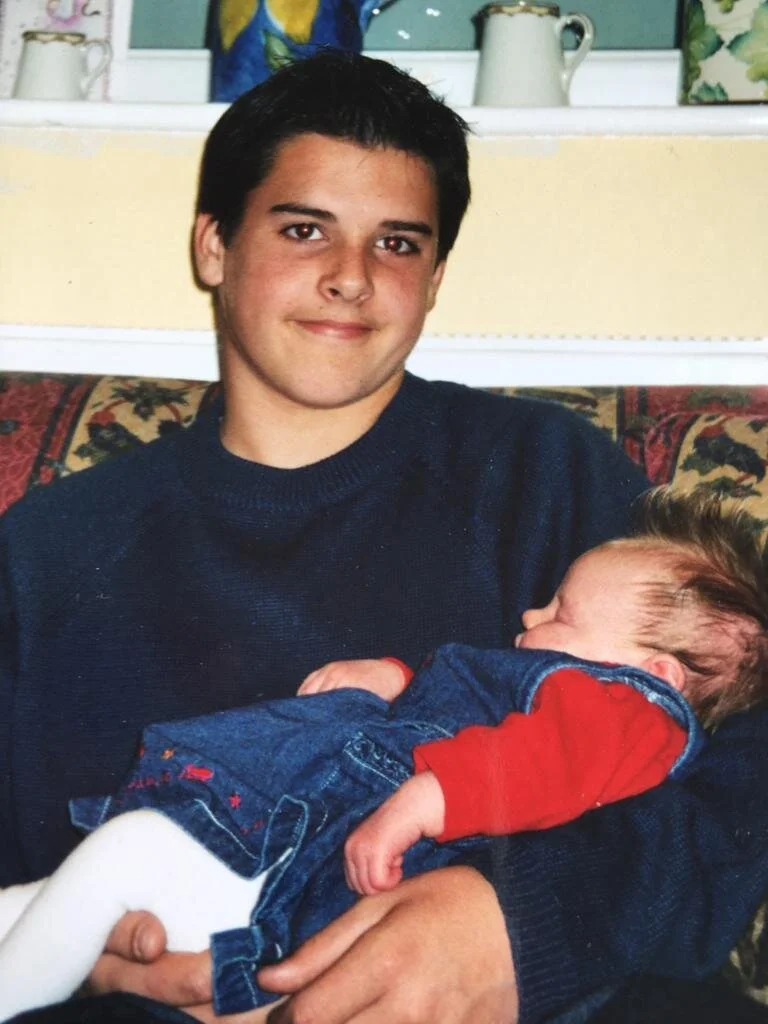

Jay’s Father, Brother & Son.

Getting Tested.

The cardiac testing took about four months to complete. Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (AC) can be really difficult to detect, so during this time we were each given several tests, including an electrocardiogram, an echocardiogram, a signal-averaged electrocardiogram, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan and an exercise test. The tests were carried out by sympathetic staff in a non-invasive way, without causing any pain or discomfort.

While the cardiac tests were ongoing, we were also contacted by the genetics team at the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital, because Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (AC) is a genetic condition. The use of genetics in medicine is still very new, and can only be used effectively when the genetic contribution to disorders such as Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (AC) is understood; in our case, genetic testing was offered to our family because doctors had already identified that Jay’s genetic make-up included the faulty genes known to contribute to Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (AC).

The decision to undergo genetic testing is deeply personal, and testing takes place only after several consultations to explain the processes thoroughly and answer any questions or concerns. We attended these consultations as a family, and together we decided to go ahead with the genetic testing. Each of us gave a blood sample and the process began.

The genetic testing took longer than the cardiac screening process, lasting for about 12 months, but eventually both sets of results were returned.

They confirmed that AC had been passed to Jay from his Dad’s side of the family, and showed that two of Jay’s four siblings had also inherited the condition, (Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (AC) is an autosomal dominant inheritance genetic condition, meaning there is a 50:50 chance of a parent passing it on to their child). Although we had chosen to have the tests and we knew the possible outcome, this news was still difficult to hear.

We were quickly reassured by the cardiology team, who explained that they would be able to protect the three affected family members by fitting them with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), a sort of mini personal defibrillator. Similar in size to a pacemaker, the ICD sits under the skin near the heart and monitors the patient’s heart rate; if the rate becomes dangerously fast or chaotic (and therefore potentially life-threatening), the ICD administers a small burst of precisely targeted electrical current. The current effectively re-sets the heart’s electrical system and restores a normal heartbeat.

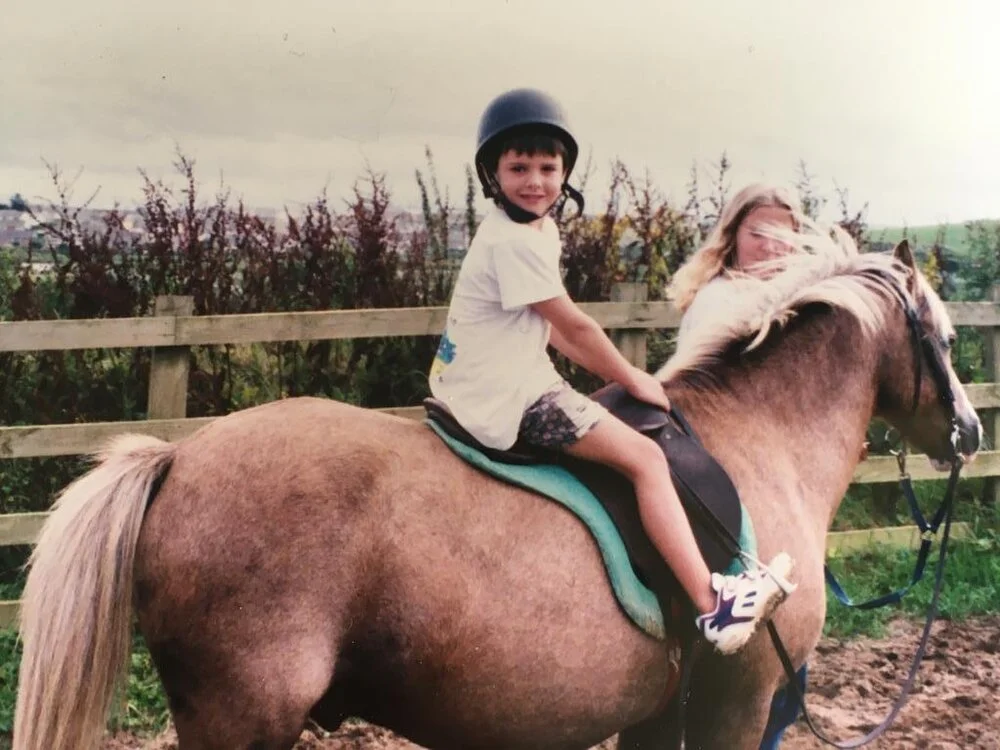

We were made aware that moving forward any children of family members with AC would need to be monitored and tested at appropriate ages in the future.

Our family will always be grateful to the cardiology and genetics teams who guided us gently and sympathetically through the testing processes, but at the same time, we wish we’d never had to meet them. Wouldn’t it be better if a simple, early-life test had flagged up Jay’s condition in time to ensure it could be managed? Jay never attended a screening event such as those carried out by the charity Cardiac Risk in the Young (CRY), but had he done so, it is likely his ARVC would have been discovered (89% of undiagnosed conditions are found using this method).

As a family, we would then have been aware of the condition, and we would have learned to live with the fact that some of us have inherited it. Most of all, Jay would still be with us.

We hope our story will encourage everyone aged 14-35 to take cardiac health seriously, and get their hearts checked. More information on cardiac screening can be found here.